Reconstructing Luzzaschi: A Hypothetical Four-Part Version of 'Ch’io non t’ami, cor mio'

What if Luzzasco Luzzaschi’s Ch’io non t’ami, cor mio, a highly virtuosic solo madrigal with keyboard accompaniment, had once existed as a four-part polyphonic work? One might wonder whether it originated as a polyphonic madrigal before taking its solo form. In this reconstruction, I explore this possibility, guided by the composer’s style and historical practices.

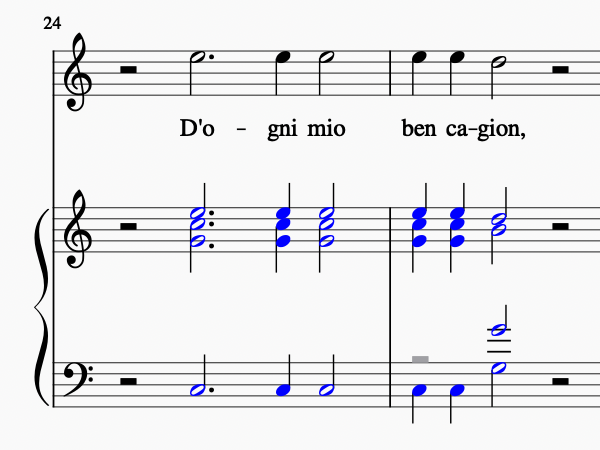

Measures 24–29 of the solo madrigal with keyboard accompaniment.

The same excerpt of the madrigal, reconstructed in its polyphonic form.

The 1601 publication of Madrigali per cantare et sonare a uno, e doi, e tre soprani by Luzzasco Luzzaschi represents a landmark in the history of Italian madrigal composition. Engraved by Simone Verovio, this collection provides insight into the musica secreta performed at the Este court in Ferrara, particularly highlighting the virtuoso singing of the Concerto delle Donne. Although published at the turn of the seventeenth century, much of the music likely dates back to the 1580s, when Luzzaschi was actively composing for these elite female singers.

Madrigali di Luzzasco Luzzaschi per cantare et sonare a uno, e doi, e tre Soprani, Roma, Simone Verovio, 1601.

The volume's innovative presentation—vocal parts with written-out diminutions in open score, accompanied by a fully realized harpsichord part—sets it apart from contemporary madrigal collections. At the same time, as Laurie Stras has argued, the notated accompaniments and vocal lines in this edition may represent a stylized or skeletal version of what was actually performed. We know that the ladies also sang with various forms of accompaniment, including one or multiple instruments such as lute, harp, or viol, or even unaccompanied—opening intriguing possibilities for modern performers.

Recently, while revisiting the three solo madrigals that open the collection (⏵︎ Aura soave; ⏵︎ O primavera; and ⏵︎ Ch’io non t’ami), I decided to arrange them for voice and a consort of viols, breaking down the keyboard accompaniment into four parts. This approach seemed logical, as the accompaniment appears to be an intabulation of a four-voiced polyphonic madrigal. Luzzaschi's writing is notably strict, consistently maintaining four voices, suggesting a highly controlled counterpoint rather than a continuo realization. But why not take it a step further and attempt to underlay the poetic text into the other parts?

Transcription and edition of Ch’io non t’ami, cor mio in the original key.

Ch’io non t’ami cor mio arranged for solo voice and consort, in the original key.

For the sake of this reconstruction experiment, I chose to work with the hypothesis that the keyboard accompaniment represents indeed an intabulation of a lost four-voice madrigal. My goal was to reverse-engineer how this hypothetical original might have sounded. Since none of the pieces in this collection have been discovered in other sources in a different form, this hypothesis cannot be definitively verified.

The first solo madrigal I chose to reconstruct in polyphonic form was Ch’io non t’ami, cor mio. This process required carefully underlaying the text while interfering as little as possible with Luzzaschi’s counterpoint. Thus, the new parts needed to be written in a way that was both idiomatic and stylistically coherent.

The soprano part will be presented without the written-out diminutions of the solo version, as the cantus in the keyboard accompaniment already provides an unornamented version. (Given that the soprano line is consistently doubled throughout the accompaniment, could it even be performed as an independent keyboard piece?).

The solo soprano part of Ch'io non t’ami is notated in a high clef (G on the second line), so I transposed it down a fourth to better suit the natural range of a vocal ensemble, as recommended by many theorists contemporary to Luzzaschi, such as Zarlino and Zacconi. Could it be that the 1601 engraved publication chose not to transpose it to highlight the virtuosic skills of the Concerto delle Dame di Ferrara, renowned for their extensive range and exceptional agility? Notably, while the soprano solo part of O primavera is also in a high clef, Aura soave is written in a C clef on the first line—the standard soprano clef for this period and style—requiring no transposition, as the range of all four voices fits smoothly in a vocal ensemble performance.

Above, the solo madrigal is shown in its original key as printed in the source, with the cantus highlighted in red, the altus in green, the tenor in blue, and the bassus in black. Below, the madrigal is transposed down a perfect fourth, based on the assumption that the hypothetical original parts would have also been notated in high clefs and intended for transposed performance:

As we know, when intabulating a vocal piece for keyboard or lute, the original note values were often altered to suit the needs of the intabulator. Long notes could be broken into smaller values to keep them sounding, or conversely, short repeated notes could be replaced by a long one in the intabulated version. Vincenzo Galilei even wrote that the intabulator should use their judgment to decide whether to rearticulate notes or omit repetitions when adapting a piece. Applying this principle, I adjusted note values where necessary to ensure a natural text setting and smooth phrasing in the reconstructed voice parts.

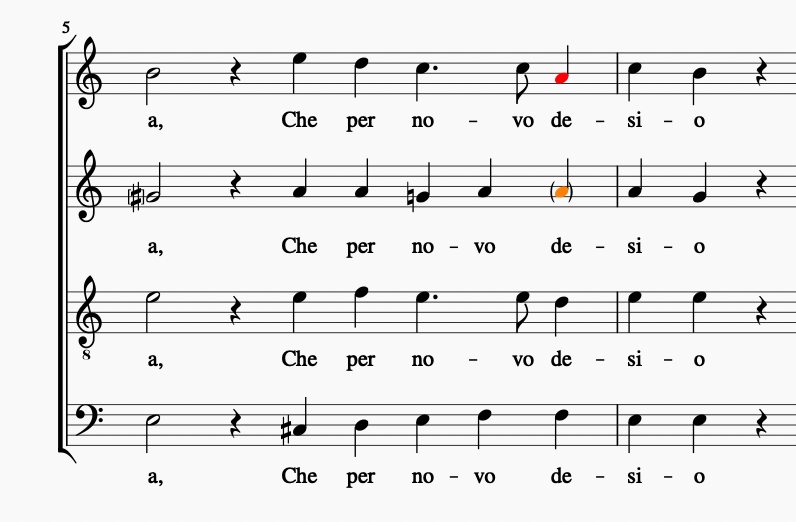

The word desio has three syllables (de-si-o), requiring three quarter notes, as seen in the cantus and altus. The tenor and bassus, however, have only two notes at this point—a quarter note and a half note, respectively. To align the syllables consistently with the upper voices, I divided the half note into two quarter notes:

Many passages feature the bass repeating a note several times in quick succession, while the right hand plays a chord for each repetition. This creates a rapid reiteration of identical chords, which, as Jack Ashworth and Paul O'Dette note in their chapter on Proto-Continuo, can feel somewhat unsettling in practice. However, if we consider the possibility that this was originally a homophonic passage from a four-voice madrigal, it no longer seems unnatural and makes the text underlaying quite easy. Could this serve as evidence that the original form was indeed a polyphonic madrigal, with the repeated notes reflecting syllabic articulation? Or were they simply restruck to reinforce the accompaniment’s harmonies?

The voices distributed in score, with the text underlaid:

In some passages, the intabulation may create the impression that certain notes are missing in some parts, or that the four voiced texture was reduced. I assume this is likely due to two voices being in unison at those moments, with the engraving omitting the doubled notes for a cleaner look. To address this, I needed to fill in these apparent gaps.

The note A' in the altus part, highlighted in orange, is not written in the source and is shown here in parentheses. I assume the engraver omitted this note since it was already present in the cantus part.

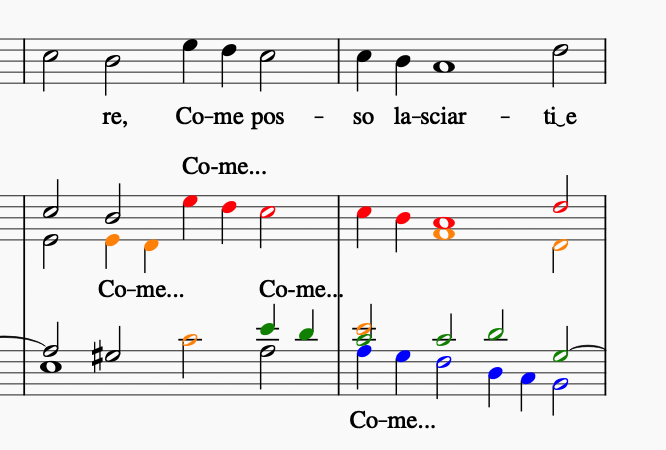

Below we have a similar case, but this time with the E' in the altus part on the second syllable of the word posso (highlighted in orange and in parentheses), which was already sounding in the tenor part. Writing an E' in the altus part seemed the obvious choice, as it is also the next note in the word lasciar:

The intabulation often places alto and tenor notes on the same staff in the left hand along with the bassus, which can sometimes obscure the voice leading. Occasionally, the altus and tenor parts cross between the staves, so we need to be attentive in identifying which note belongs to each voice.

In passages with imitative polyphonic entries, it is important to observe the imitations between the voices to properly underlay the text in an imitative manner. Note that the notes corresponding to the altus part (highlighted in orange) appear sometimes in the upper staff and sometimes in the lower staff.

And here is the result of the transcription of this imitative polyphonic passage, with the text underlaid in each part:

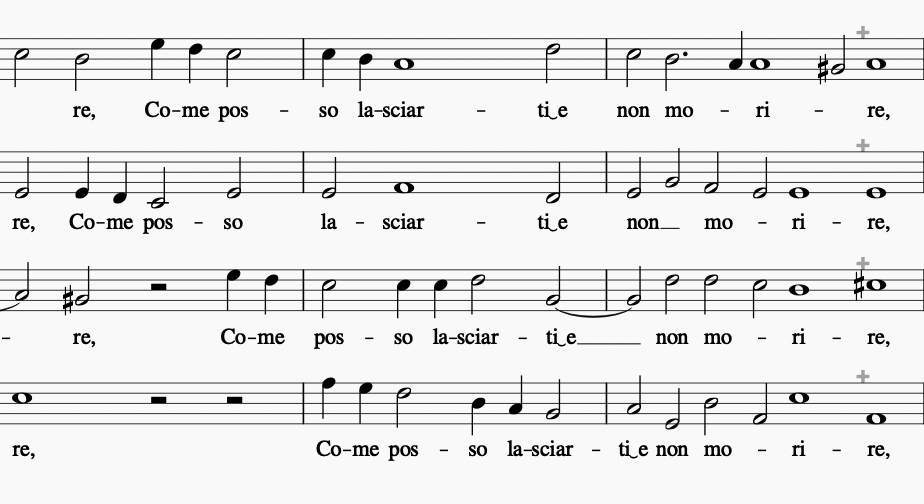

With some imagination and a bit of reverse engineering—by breaking down the polyphonic keyboard accompaniment, removing the written-out diminutions, transposing it down a fourth, and underlaying the poetic text in all four voices—voilà! Here is a highly speculative yet (hopefully) convincing reimagining of this exquisite composition:

While this version remains conjectural, it is grounded in historical information and compositional logic. Through this reconstruction, I hope to imagining how Luzzaschi’s fascinating madrigals might have sounded before being presented in their highly virtuosic solo versions—perhaps even offering one more possibility for performing them to modern audiences.

References:

Maniates, M. R. (1979). Mannerism in Italian music and culture, 1530-1630. Manchester University Press.

Stras, L. (2018). Women and music in sixteenth-century Ferrara. Cambridge University Press.

A performer’s guide to Renaissance music (2nd ed.). (2007). Indiana University Press.

Luzzaschi, L. (1965). Madrigali per cantare e sonare, a uno, due e tre soprani (1601) (A. Cavicchi, Ed.). Monumenti di musica italiana, ser. 2: Polifonia, 2. Brescia & Kassel.

Luzzaschi, L. (1980). Madrigali per cantare e sonare a uno, doi, e tre soprani: Roma 1601 (Vol. 35, Archivum musicum. Collana di testi rari). SPES.

Early Music Sources. (2019, May 9). Luzzasco Luzzaschi: Madrigali per cantare et sonare (1601) [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HpFrBUQUaNM