English Mad Songs

In the 17th century, English mad songs emerged as a significant musical genre, blending poetry, drama, and music to produce a deeply emotional experience. These songs were typically written in a highly expressive style, with lyrics that often depicted themes of love, loss, jealousy and madness. Musically, they were characterized by their use of complex harmonies and intricate melodic lines that were designed to convey the dramatic intensity of the lyrics.

Rubens, Peter Paul. "Venus and Adonis." Probably mid-1630s. Oil on canvas. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

Some of the most well-known composers of English mad songs during this period were ⏵︎ John Eccles, Daniel Purcell, John Weldon and John Blow. Eccles, in particular, was known for his use of unconventional harmonies and for his ability to create a sense of emotional intensity in his music.

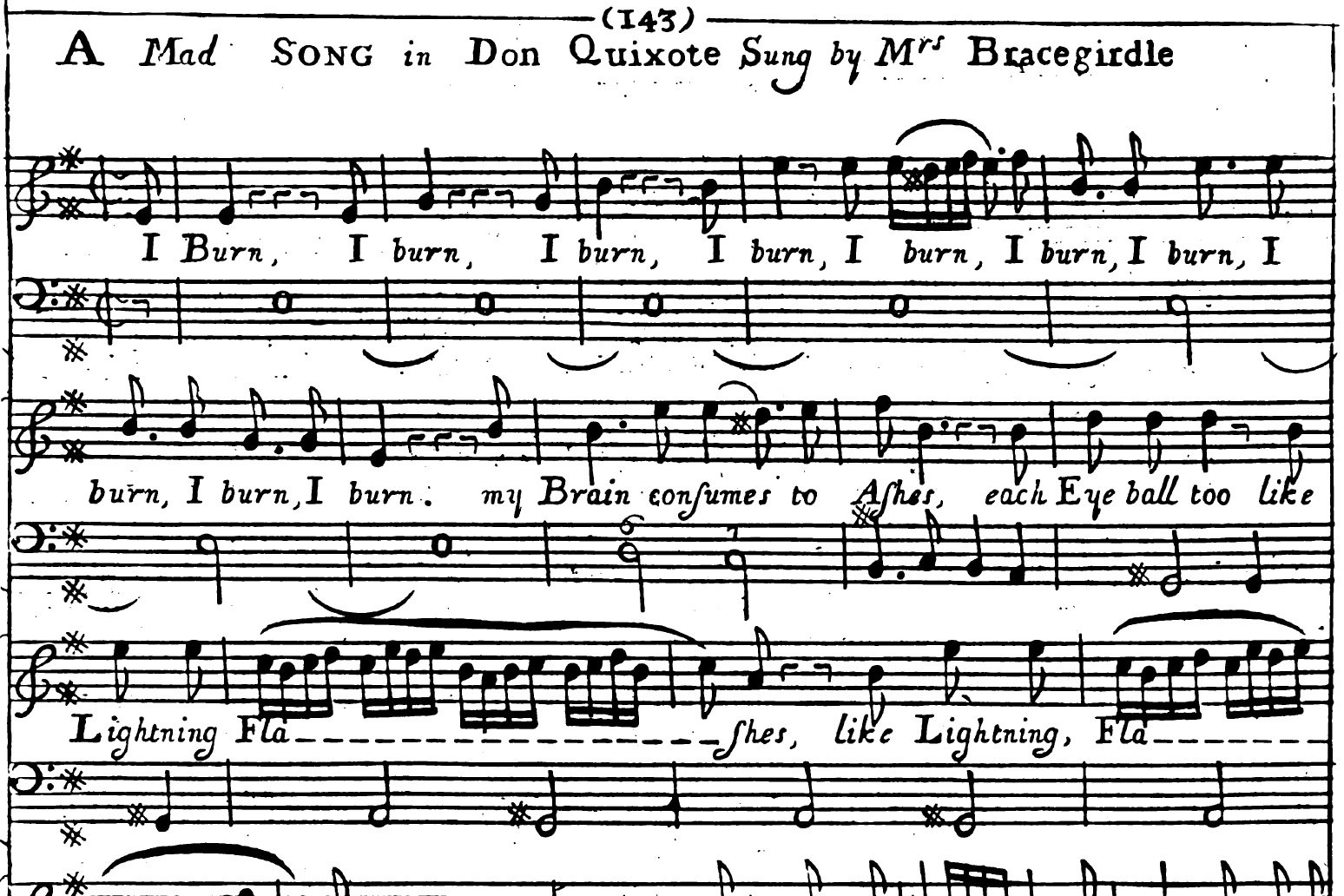

Eccles' ⏵︎ “I burn, my brain consumes to ashes” features highly dramatic lyrics, and equally intense music that describe the passionate feelings of love and longing experienced by the speaker. This innovative combination of speech and song was a new benchmark for dramatic song, and “I burn, my brain consumes to ashes” became a triumphant success overnight, thanks to the combined efforts of playwright Thomas D'Urfey, composer John Eccles, and actress Anne Bracegirdle.

John Eccles’ I burn, my brain consumes to ashes from A Collection of Songs published by John Walsh and John Hare (1704).

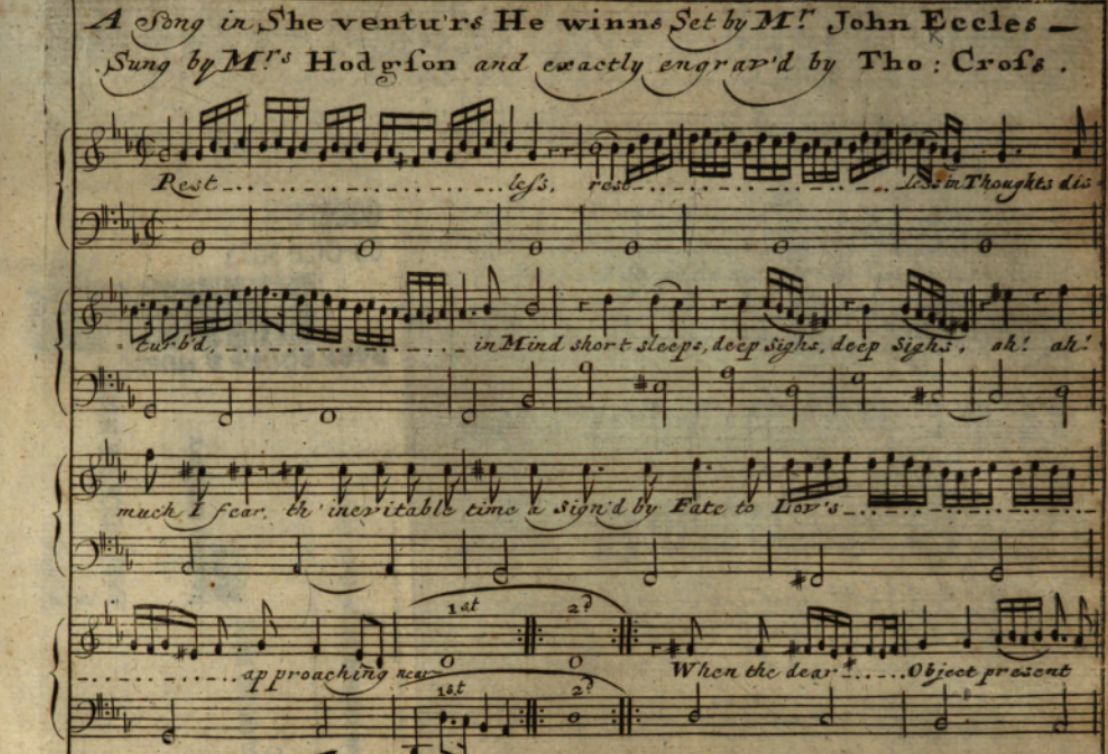

Eccles’s setting of ⏵︎ “Restless in thought, disturb’d in mind” begins with a pair of melismas over a sustained G in the bass. Notably, the initial six measures lack figured bass notation, which contrasts with the detailed bass figures provided for other sustained passages in the continuo line. This absence emphasizes a sense of harmonic stability. Despite the intricate melismas on the word "Restless," which feature active motion, they consistently return to the initial note, with the final group of sixteenth notes replicating the first. This structural consistency reflects the lyrics, highlighting the speaker's inescapable situation: she is 'fated' to love, her heart is 'enslav’d,' and she is physically unable to leave whenever he is near. Even in the section set to "disturb’d," which introduces more harmonic space by moving towards B-flat, the harmonic progression largely relies on a dominant pedal.

Juliana’s lament follows the structure of mad songs, with several short, contrasting sections. After the striking opening, Eccles incorporates brief imitative exchanges between the singer and continuo, along with repetitive emphasis on single words, such as 'no,' which was frequently used in the music of the time. The final section, written in cut time, starts with a somewhat lively character. However, the solemnity of the written-out second ending creates a stark contrast, emphasizing a sense of futility as conveyed by the word 'in vain.'

Restless in thought, A Song in She Venturs He Winns, sung by Mrs. Hodgson, from A Collection of Songs, 1704.

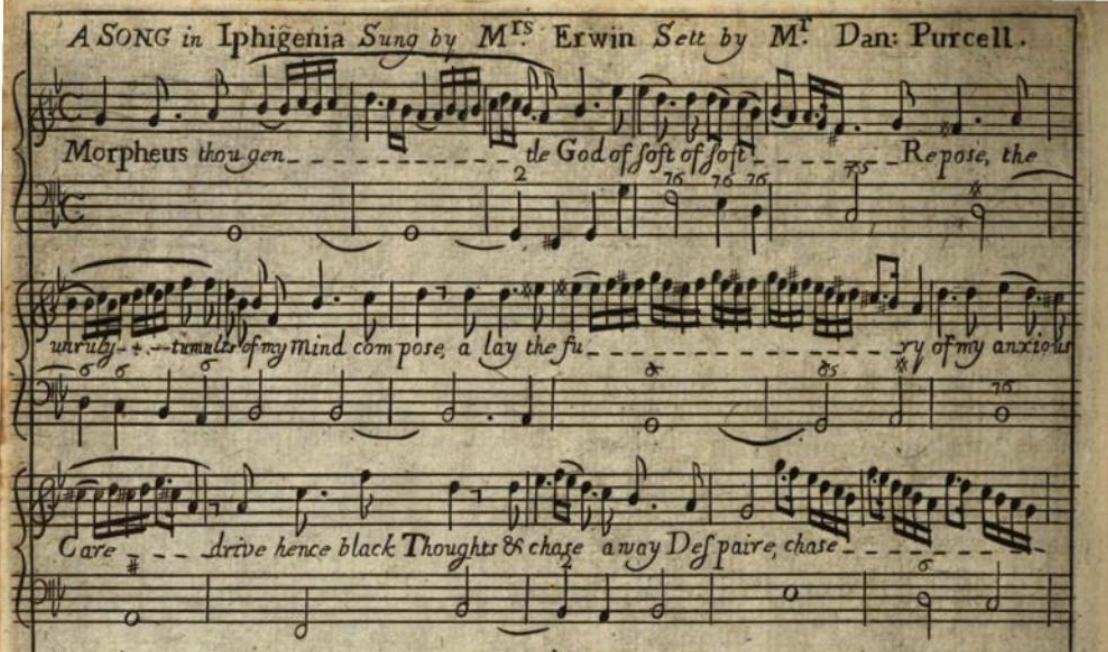

The mad song ⏵︎ “Morpheus, thou gentle god of soft repose” vividly conveys the lonely suffering of the jealous Eriphyle in the play Ephigenia. Composed by ⏵︎ Daniel Purcell and performed by the renowned singer Mrs. Erwin, who was not a character in the play—a common practice in both German and English theater of the time—the piece contrasts sharply in its musical structure.

D. Purcell arranges the song in brief, contrasting sections, creating a dramatic effect akin to a mad song. Despite invoking the calming presence of Morpheus, the final stanza reveals a stark departure from tranquility: “I rage, I rave, I burn, my Soul's o' fire.” The song serves as a showcase for Mrs. Erwin, who had several notable pieces composed for her during that season.

Morpheus, thou gentle God from A Collection of the choicest Songs & Dialogues. United Kingdom: I. Walsh, 1705.

Overall, English mad songs were an important and influential genre of music during the 17th century, and they continue to be appreciated and performed to this day. With their highly dramatic content and intricate musical structures, they represent a powerful form of musical expression that remains relevant and compelling to modern audiences.

If you're interested in exploring the world of English mad songs during the Baroque period, be sure to check out Anthony Rooley's essay for more information. Additionally, don't forget to visit my YouTube channel where I have curated a playlist of some of the most exciting and energetic ⏵︎ English Mad Songs from the Baroque era. And for those who are musically inclined, you can find sheet music for mad songs by John Eccles, Daniel Purcell, John Weldon, and other Baroque composers at my virtual store.

Reference:

Rooley, A. (2007). English Song: Mad Song. Schola Cantorum Basiliensis - Musik-Akademie der Stadt Basel. Retrieved from https://www.forschung.schola-cantorum-basiliensis.ch/dam/jcr:6b43bb09-c94f-4968-8909-60a55d3c58bd/Rooley_English_Song_72dpi.pdf

Lowerre, K. (2017). Music and Musicians on the London Stage, 1695-1705. United Kingdom: Taylor & Francis.