17th Century Italian Laments

Lamento is a musical genre that emerged in Italy in the early 17th century, during the transition from the Renaissance to the Baroque period. It is characterized by its intense expression of sorrow, grief, and lamentation, often featuring a solo voice accompanied by a basso continuo. The text of a lamento typically describes a tragic event or situation, such as the death of a loved one, the loss of honor, or the frustration of unrequited love. Through its emotive melodies and harmonies, the lamento aims to move the listener to tears and evoke a sense of empathy and compassion.

“Bacchus and Ariadne” painting by Alessandro Turchi (L'Orbetto), c. 1630. National Gallery in Prague.

Many composers of the early Baroque period were drawn to the expressive potential of the lamento, including Claudio Monteverdi, Giacomo Carissimi, Barbara Strozzi, and Luigi Rossi. One of the most famous examples of the genre is Monteverdi's ⏵︎ Lamento d'Arianna from his opera L'Arianna, with its expressive melodic lines and intricate chromatic harmonies perfectly capturing the deep despair of the protagonist.

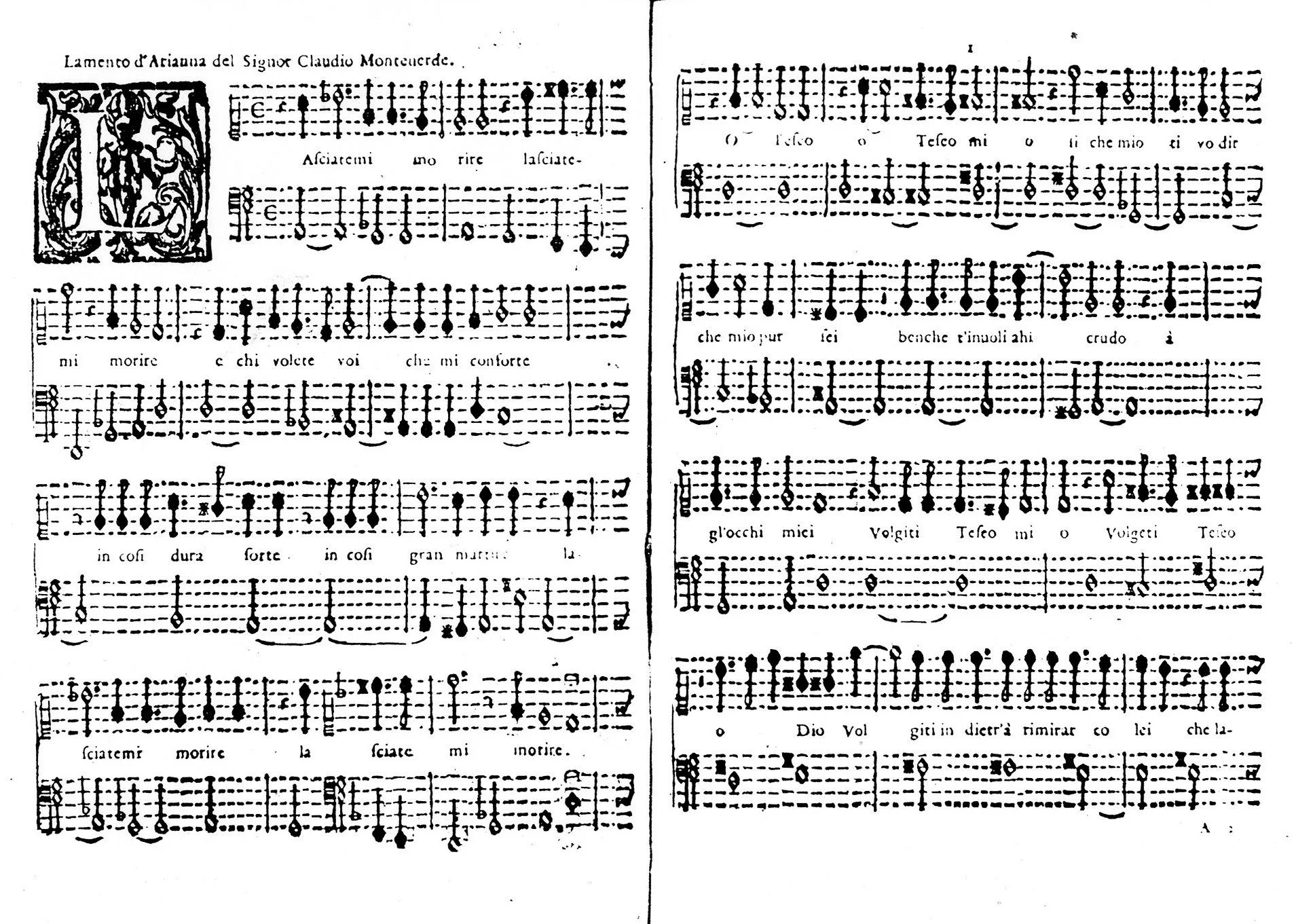

First two pages of the first edition of Monteverdi’s Lamento d’Arianna, published by Gardano in Venice in 1623.

Monteverdi employs a variety of declamatory styles, matching the text's different sections. Notably, the dissonances between the voice and the bass in both statements of "lasciatemi" reflect Ariadne's increasing anguish. In other parts of the lament, Monteverdi uses repeated pitches in the vocal line, supported by harmonies that remain relatively static.

Ariadne’s climactic outburst of anger in the fourth section is again marked by declamation on repeated notes, building intensity through rising pitches and an accelerating pace, culminating in rapid semiquavers at "le voragini profonde." The supporting harmonies emphasize the passage's climactic nature, with Monteverdi diverging from the lament's tonal foundation. Monteverdi's sensitive pairing of musical detail with Rinuccini's poetry creates a powerful, expressive language for the grieving soloist.

Musical and textual features of Monteverdi's Lamento d'Arianna reappear in numerous laments based on classical characters by later composers in the following decades.

A notable example is Francesco Costa’s 1626 solo setting of ⏵︎ Pianto d'Arianna. Costa's setting features a slow-moving bass line that shifts only once or twice per poetic line, paired with a predominantly stepwise or monotonal vocal line that facilitates a more lyrical delivery. Costa incorporates several embellishments, such as the trillo, and employs a cadential cliché involving a dotted rhythm and slur on the final syllable of a line. He also introduces a brief passage in triple meter. He cuts to Rinuccini's text, specifically before and after Ariadne’s rage, isolating her anger into a separate musical section.

As early cantatas began to emerge, particularly from Roman composers in the 1630s and 1640s, the purely recitative lament evolved into a hybrid form, still primarily recitative but incorporating brief arioso or aria-like sections.

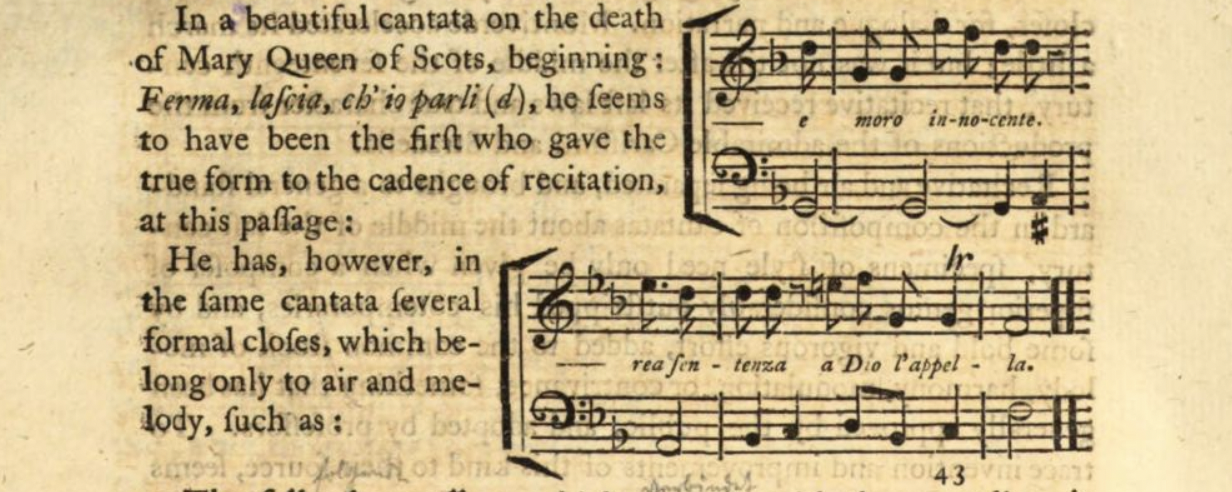

British Library, Harley MS 1265 (ff.1r-12v), a volume of musical compositions cataloged by Humphrey Wanley, includes Giacomo Carissimi’s ⏵︎ “Ferma, lascia ch’io parli”, also known as Lamento di Maria Stuarda. A note accompanying the manuscript mentions that Carissimi was considered the best composer of church music in Italy during his time. This cantata is one of the more interesting works inspired by Mary's tragic end, and Charles Burney includes samples of it in his History of Music (vol. iv. p. 142).

Lamento di Maria Stuarda, British Library, Harley MS 1265, f.1r.

Carissimi’s Lamento, composed around 1650, is based on a text likely written by Giovanni Filippo Apolloni. The cantata portrays the Catholic Queen, Mary Stuart, addressing her executioner before her death. The opening line, “Ferma lascia ch’io parli” (“Stop, let me speak”), captures the queen's final moments, followed by an aria in adagio to the words “A morire, a morire” (“To die, to die”). Carissimi’s musical setting of this emotionally charged text follows a tripartite cantata form. It opens with an extended arioso recitative in 4/4 time, followed by an adagio aria in 3/4, and concludes with a return to 4/4 recitative.

Between the thrice-repeated refrain “A morire”, Mary asserts her innocence and decries the injustice of her situation. She also expresses love and gratitude for her ladies-in-waiting while condemning London and its ruler, Elizabeth I, whom she describes as the "second Jezebel." Most of the text is set in the first person, though the concluding section shifts to the third person. At this point, the performer becomes an omniscient, angelic narrator who affirms that the unconquered Queen Mary has safely reached her heavenly destination.

Burney, Charles. A General History Of Music: From The Earliest Ages to the Present Period. United Kingdom: Author, 1789.

The frequent modulations in the recitative sections contrast with the more stable aria in the middle. This structural pattern mirrors the shifting emotions and themes within the Lamento. The modulations are balanced by a largely syllabic setting of the text, which is unusual for Carissimi, who typically favored more elaborate melismas. In this work, the melismas are sparing but significant. For instance, the longest melisma is on the word “vaglion” (meaning “no longer”), and the second longest appears on “serbar” (meaning “preserve”). These moments emphasize Mary’s realization that her political status and crown can no longer save her. Carissimi, like many of his contemporaries, viewed Mary’s death as an act of religious persecution, but his setting also highlights the political injustice she suffered at the hands of Elizabeth.

Another type of lament developed mid-century, distinguished by its complete setting in aria style and often structured over a descending tetrachord. Rosand observes that in the 1640s and 1650s, the descending minor tetrachord became a defining feature linked to the Baroque lament. Monteverdi's ⏵︎ Lamento della Ninfa, set to another Rinuccini text, stands out among early Baroque laments for its emotional power and its importance in shaping the genre, comparable to Arianna. Published in Monteverdi's Ottavo Libro in 1638, this lamento is structured around a descending tetrachord ostinato, which facilitates a a dynamic interplay between the voice and bass line, creating dissonances in melody, rhythm, and texture, which are heightened by the persistent downward motion in the minor mode, evoking endless sorrow.

The Lamento della Ninfa is part of a broader trend from the 1630s, where many composers utilized the descending tetrachord. Notable examples include Giovanni Felice Sances's ⏵︎ Usurpator tiranno, Luigi Pozzi's ⏵︎ Così dal lungo sangue sparso, Francesco Cavalli's ⏵︎ Lamento di Egisto (or ⏵︎ Vieni, vieni in questo seno), Antonio Cesti's ⏵︎ Disserratevi abissi (featuring a chromatic variation of the minor descending tetrachord), and Francesco Lucio's ⏵︎ Fuggi pur, o crudele. These works, found in contemporary aria collections and operas, helped establish the descending tetrachord as a symbol of lamentation and grief throughout the Baroque period.

For those who are interested in exploring the genre of lamento further, I have created a curated playlist on my YouTube channel, which features a selection of beautiful and moving laments by composers of the 17th-century Italian Baroque. The playlist can be accessed by clicking on ⏵︎ 17th Century Italian Laments. Furthermore, if you are interested in acquiring transcriptions of these laments, they are available for purchase on the virtual store of my website.

References:

Bukofzer, M. (1947). Music in the Baroque Era. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, Inc.

Carter, T. (2004). Lament. Grove Music Online. https://doi.org/10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.article.16184

Carter, T. (2013). The Oxford History of Western Music, Volume II: Music in the 17th and 18th Centuries. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Burney, C. (1789). A General History Of Music: From The Earliest Ages to the Present Period. United Kingdom: Author.

Hawkins, J. (1858). A General History of the Science and Practice of Music. United Kingdom: J.A. Novello.

Rosand, E. (1979). The Descending Tetrachord: An Emblem of Lament. The Musical Quarterly, 65(3), 346–359. http://www.jstor.org/stable/741489