I-Bc MS Q.43: 17th Century Roman Lamentations for Holy Week

Jeremiah Lamenting the Destruction of Jerusalem, 1630, by Rembrandt. Oil on panel, Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, Netherlands.

In seventeenth-century Rome, Holy Week witnessed the full variety of musical expression, from chant through polyphony to monody. The settings of the Lamentations of Jeremiah for performance during Holy Week were widely diffused throughout the Seicento, which saw the diffusion of the repertory at the height of the Catholic Reformation.

While these works adhered to the basic requirements of Lessons, such as the use of Hebrew letters and the line "Jerusalem convertere" at the end, they departed significantly from the traditional stile antico. The emotionally charged content of the Lamentations text provided composers with numerous opportunities for expressive text setting, including chromaticism and free use of dissonance. This, along with a tendency towards arioso form, resulted in a highly poignant and dramatic style that was reminiscent of the lament in opera, oratorio, and cantata.

With its twenty-three Lessons, I-Bc MS Q. 43 is a "repository of Lessons" as opposed to neat cycle. All the lessons are solo settings except for two duets for soprano and mezzo. About half the contents are anonymous, with three settings by G. F. Marcorelli, and two settings each by Giacomo Carissimi and Carlo Rainaldi. Single Lessons are attributed to Frescobaldi, Carlo Caproli, and "M.M.," probably Marco Marazzoli; the other thirteen have no composers and no concordances, and the music must date from the middle third of the century. Hans Joachim Mary has observed that these musicians were all active as organists, singers, and maestri di cappella in Rome in the 1630s; he has therefore dated the source ca. 1640.

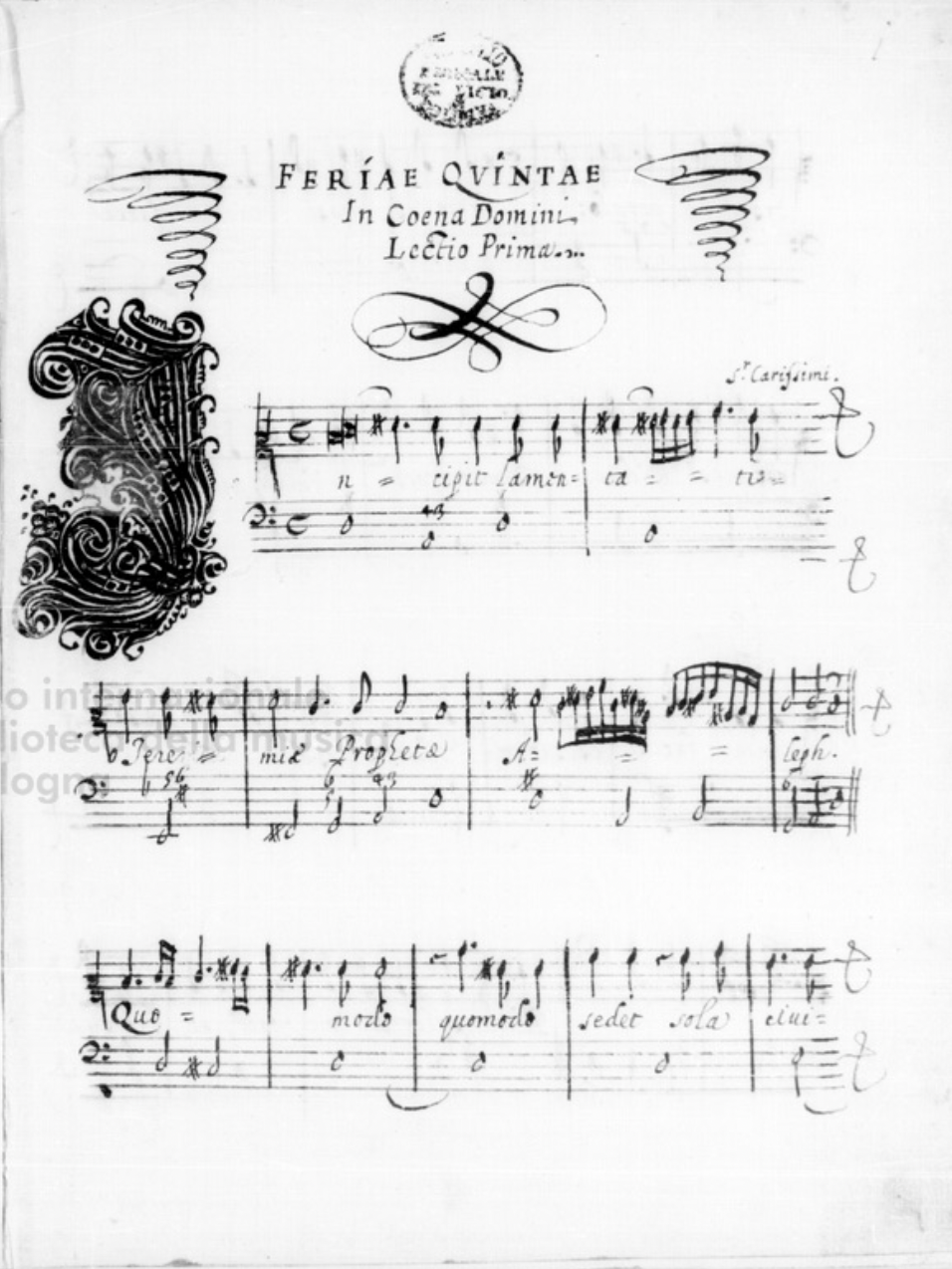

Lectio Prima, Feriae Quintae In Coena Domini, by

Giacomo Carissimi (c.1605-1674).

From Museo internazionale e biblioteca della musica di Bologna, MS Q.43, ff.1v-5r.

The Lessons are followed by six Passion/penance pieces in the vernacular (including a contrafactum placing Monteverdi's Lamento d'Arianna in the voice of Mary Magdalen), and six early oratorios; given the six weeks of Lent, this suggests a quaderno di Quaresima, a book with all the extra music for the season.

Tenebrae as in Caerimoniale episcoporum, Rome, 1600. From Special Collections Research Center, University of Chicago Library.

Carissimi is credited with contributing to the settings of the Lectio Prima ⏵︎ (“Incipit Lamentatio Jeremiae prophetae”) and the Lectio Seconda ⏵︎ (“Vau. Et egressus est a filia Sion”). The original scribe attributed these works to "Sr. Carissimi" on the first, and "J.C." on the second lesson, respectively. Carissimi's monodic lamentations demonstrate a less extravagant use of the solo voice. These pieces exhibit a style closest to parlando recitative in Carissimi's sacred music. While the writing is responsive to the text's demands, and the harmonic style enhances its pathos, there is none of the melodic inventiveness typical of his arioso style. Flourishes are generally reserved for the introductory Hebrew letters, and in some sections these occur not in the voice but in the continuo.

The surface chromaticism and ornamentation of Frescobaldi's Lesson have parallels in his solo motets in Liber secundus diversarum modulationum (Roma, 1627). His Feriae Quintae/Lectio Terza ⏵︎ (“Jod. Manum suam misit hostis”) is rhetorically clear. Cast on D durus, the Lesson demarcates verse structure by pitch; in I: II, the sub-verses move to F, then A, with another weak cadence back to D at "facta sum vilis," without grinding dissonances or solecisms. Precisely at "O vos omnes" and "si est dolor sicut dolor," of I:I2, Frescobaldi turns to chromaticism, saving the highest vocal register around the high G5 for "De excelso misit ignem".

All of the lamentations in the Bolognese Codex are mainly written in the 'stile recitativo': syllabic, taking into account the declamatory rhythm and syntactic division of the text. Particularly emotional words (such as 'affliciotionem', 'dissipatus', 'dolor') are emphasized through musical-rhetorical figures. For a particularly striking example, Frescobaldi composes the words 'si est dolor sicut dolor meus' (Lamentations I:I2) not only using the 'passus duriusculus', but also by increasing its emotional content through a rhythmic division achieved by shifting the word accents. This Lesson provides a dignified and expressive account of its poignant text, and it partially contradicts Antimo Liberati's censure of Frescobaldi as a composer of sacred vocal music in his 1685 letter from Rome. As the manuscript appears to date from around 1640-1650, it is plausible that Frescobaldi's Lamentation setting represents one of his later works and was meant to be performed at the Crocifisso.

Lectio Terza, Feriae V in Coena Domini, by Girolamo Frescobaldi (1583-1643).

From Museo internazionale e biblioteca della musica di Bologna, MS Q.43, ff.7r-10r.

Marcorelli’s solo setting of the Sabbati Sancti/Lectio Seconda ⏵︎ (“Aleph. Quomodo obscuratum est aurum”) resorts only to surface chromaticism in a stable tonal structure. He had spent time in Umbria and Rome before working at Rome's Chiesa Nova in 1646-47, whence the piece might stem. Marcorelli's approaches to his duet setting of the same verse are less virtuosic but more varied rhetorically.

In summary, MS Q.43 offers valuable insights into the diverse and vibrant musical culture of 17th-century Rome, particularly in the context of Holy Week. Through its range of compositions and composers, from anonymous works to compositions by notable masters such as Carissimi, Marcorelli, and Frescobaldi, the manuscript serves as a testament to the rich tradition of singing settings of Lamentations of Jeremiah, which was an essential part of the liturgical practice of the time.

References:

Dixon, G. (1986). Carissimi. [Mit Noten.] - Oxford [usw.]: Oxford Univ. Press. VII, 84 S. 8°.

Hammond, F. (2002). Girolamo Frescobaldi. Palermo: L'Epos.

Kendrick, R. L. (2014). Singing Jeremiah: Music and Meaning in Holy Week. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Marx, H.J. (1971). Monodische Lamentationen des Seicento. Archiv für Musikwissenschaft, 28(1), 1-23.

The Cambridge History of Seventeenth-Century Music. (2005). Volume 1. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.