Love Letters in Music: Lettere Amorose from 17th Century Italy

Johannes Vermeer, Lady Writing a Letter with her Maid, c. 1670–1671, oil on canvas, National Gallery of Ireland, Dublin.

Letter writing during the early modern period encompassed both literary and non-literary, public and private, aristocratic and popular cultures in a way that no other writing practice did. Love letters, in particular, have captivated the hearts and minds of people throughout the ages. Although the form, medium, and content of love letters may have changed over time, their primary purpose remains unchanged: to convey intense emotions.

Music provides its own examples of love letters. In this text, we will delve into the subgenre of “Lettera amorosa” in music, which emerged in the Italian Baroque era of the 17th century. We will explore its historical context, its literary and musical features, and present some notable works to illustrate its significance.

The emergence of the love letter in music can be traced back to the development of monody, a vocal style characterized by a single vocal melody accompanied by a simple basso continuo, allowing for greater expressive freedom and highlighting the importance of text.

During the late sixteenth and seventeenth centuries in Italy, collections of Epistole eroiche, or heroic letters, “written” by characters from Ovid's Heroides, such as Dido, Ariadne, Deianira, Medea, Penelope, and others, were widely popular. Many of these letters, translated into Italian and published in collections, relate to solo laments in seventeenth-century opera and cantata.

Gabriel Metsu, Man Writing a Letter, 1662-65, oil on canvas, National Gallery of Ireland.

The personal letter arose as a new literary form in the Renaissance, involving a more personal and emotional style of writing. This tradition continued into the Baroque era, incorporating its rhetorical principles. The texts used for both operatic laments and monodic love letters are related in their subject matter and musical style, although laments often recount historical events or dramatic actions that are quite distant from those found in letter writing.

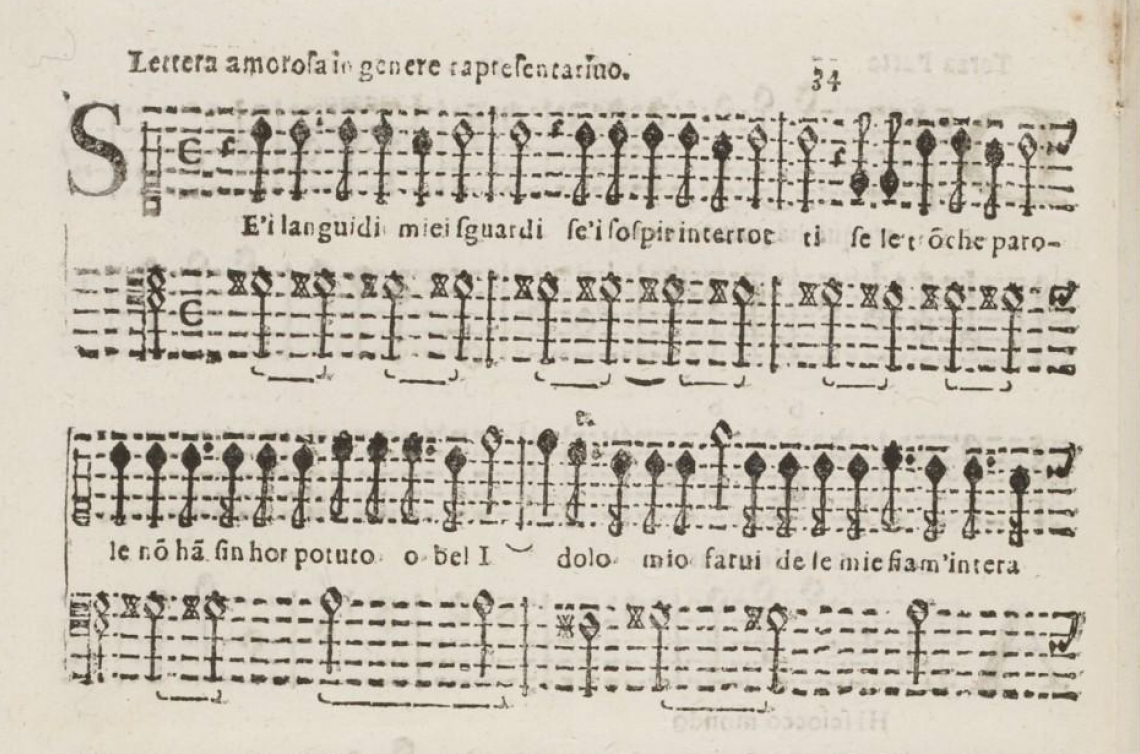

In his Settimo Libro de Madrigali (1619), Monteverdi published two works in this so-called “genere rappresentativo,” long works in recitative style for solo voice and continuo. The first, ⏵︎ “Se i languidi miei sguardi,” is a poetic love letter by the marinist poet Claudio Achillini. The speaker is depicted in the act of composing his response, and the musical language of the stile recitativo reflects his effort to find the right words. Achillini's attention is not on presenting a vivid portrayal of his lover's feelings. Instead, he directs his focus towards his beloved's hair, eyes, and mouth in a passage overflowing with various conceits and metaphors. In Achillini’s trope, the flames become words, and a heart is distilled in ink. The expressive melisma on the word "cor" effectively depicts the heart's transformation into ink, and reveals some of Monteverdi's most poignant late monodic style.

“Se i languidi miei sguardi” (Lettera amorosa in genere rappresentativo) by Claudio Monteverdi. Text by Claudio Achillini.

From Concerto: settimo libro de madrigali, Venice, Magni, 1619.

The second work, ⏵︎ “Se pur destina,” is termed a “Partenza amorosa” and, though a later printing (1623) of both pieces renames it a “Lettera amorosa,” it clearly sets forth not a letter but the parting words of a lover to his beloved. The author of the poem is Ottavio Rinuccini. Those are the most extended monodies Monteverdi ever conceived outside of an actual theatrical situation. Nino Pirrotta notes that these love letters are “strictly speaking, recitatives” and suggests that Monteverdi's use of the genre reflects his nostalgia for opera. It is possible that admiration for Monteverdi's works may have led other composers to follow his example and create similar “lettere”, placing it on the verge of initiating the tradition of the love letters in music.

D'India's monodic setting of Marino's lettera skips most of the poem and begins with the supplication for the lover's return at the line ⏵︎ “Torna dunque, deh torna.” In Le Musiche, Libro Quarto (1621), the piece is prefaced by the title “lettera amorosa del Cavalier Marini,” presumably included since the text was not yet published. The setting of a new poem by Marino would suggest a close connection between the composer and the famous poet. The letter goes on for many lines, as the lover alternates between anger and despair, much like the paths Arianna and Dido took. D'India's lettera is in a recitative style, and thus the music usually complements the natural inflections of the text. Occasionally, however, the composer uses the percussive nature of recitation in a way that reflects the structure of the text more than the specific meaning of the words.

Filippo Vitali's “Misero, e pur convien” from Madrigali et altro generi di canti, published in 1629, is a clear imitation of Monteverdi's lettera. In his description of it, Vitali slightly changes Monteverdi's earlier wording of “Lettera amorosa a voce sola in genere rappresentativo e si canta senza battuta” to “Lettera amorosa in genere rappresentativo. Voce sola e si canta senza battuta.” Although following Monteverdi as his model, Vitali, being a Florentine, may have been particularly aware of Caccini’s “Amarilli” motif. Once the piece gets underway, he slips in a clear “Amarilli” reference on the words “O Clorinda incostante.”

The melancholic and intimate lines of ⏵︎ “Vanne, o carta amorosa” from Arie musicali, Libro Secondo, 1630, move within the scope of Monteverdi’s lettere amorose, taking the poetic form of a madrigal. In contrast to Monteverdi's “Se i languidi miei sguardi,” Frescobaldi's “carta amorosa” features fewer variations in pacing and larger-scale contours. However, it does incorporate more rests within verses and a less monotone recitation. Notably, Frescobaldi cleverly poses and answers a riddle dear to the Baroque, by making sing a lover who “dies in silence”. While following the same style as Monteverdi, Frescobaldi goes a step further by allowing for a wider tonal range in the melody.

Music titled “lettera amorosa” continued to be composed even in the later part of the century. Examples include cantatas by Alessandro Stradella, Giacomo Carissimi and Atto Melani. It's interesting to observe how the love letter assumes real corporeality in these texts: the letter itself becomes a tangible object, evoking the image of ink transformed into “blood” or “tears”, and the words into “notes of grief”. The imagery of blood used as ink was very widespread in the Baroque era.

In these later examples, many composers presented extended pieces with longer texts, often multi-sectional, with a variety of moods and styles. Shifts from duple to triple meter, or from recitative to arioso style, served to articulate the individual sections, which were often extended through repetitions of music and text. This is evident in Stradella's ⏵︎ “Sopra candido foglio” (Lettera a bella donna crudele). By addressing the letter not to the beloved, but to the “cruel beautiful lady,” the writer adds a touch of resentment for her indifference, introducing a nuanced layer of depth and complexity to the message. Even in its “modernized” form with two recitatives and two arias, which would become typical of the cantata genre in the coming decades, Stradella's lettera retains points of contact with the proto-Baroque model of the love letter.

“Scrivete, occhi dolenti” by Giacomo Carissimi. From I-Bc MS X.235; Text by Francesco Melosio.

Carissimi's setting of Francesco Melosio’s lettera ⏵︎ “Scrivete, occhi dolenti” shows how the recitative style of Monteverdi moves towards a clearer division of arias and recitatives. The poet who silently endures his ill-fated love implores his eyes to write his torments with tears as ink on the page of his face. He hopes that the beloved woman will read the letter and respond with a short reply of life or death, if she holds any pity in her heart.

Atto Melani’s setting of ⏵︎ “Scrivete, occhi dolenti” also exhibits many characteristics of the mid-Seicento cantata, including the alternation of recitative and aria-like passages. It is scored for solo voice and basso continuo and opens in a neutral duple meter, with long-held bass notes essential to the recitative style. But at the words, “I burn, I weep, I sigh, and yet I do not speak,” the meter shifts to a dance-like rhythm.

The lettere amorose in music can still resonate with contemporary audiences. The themes of love, longing, and heartbreak explored in these works are universal and timeless. Moreover, the expressive power of the music, which aims to complement and enhance the emotional content of the text, can still move and captivate modern-day listeners. The lettera amorosa can be a valuable addition to a concert program, offering a window into the musical and cultural world of the Baroque, while also providing an emotional and intellectual connection with the audience.

References:

Degrada, F. (1997). Tre "Lettere amorose" di Domenico Scarlatti. Il Saggiatore musicale, 4(2), 271-316. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/43029447.

Fabbri, P. (1985). Monteverdi. Italy: EDT/Musica.

Fortune, N. (1953). Italian Secular Monody from 1600 to 1635: An Introductory Survey. The Musical Quarterly, 39(2), 171-195. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/739938.

Giles, R. H. (2016). The (un)Natural Baroque: Giambattista Marino and Monteverdi’s Late Madrigals (Doctoral dissertation). University of Toronto. Retrieved from https://tspace.library.utoronto.ca/bitstream/1807/73002/1/Giles_Roseen_H_201606_PhD_thesis.pdf

Giovani, G. (2017). Col suggello delle pubbliche stampe. Storia editoriale della cantata da camera. Roma: SEdM. Retrieved from

Hammond, S. L. (2012). The Madrigal: A Research and Information Guide. Ukraine: Taylor & Francis.

Holzer, R. R. (1990). Music and Poetry in Seventeenth-century Rome: Text. United States: University of Pennsylvania.

Tomlinson, G. (1982). Music and the Claims of Text: Monteverdi, Rinuccini, and Marino. Critical Inquiry, 8(3), 565-589. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/1343266.