L’Air espagnol en France: Spanish Airs de Cour from 1578 to 1668

From the last decades of the 16th century through the mid-17th century, a fascinating blend of French and Spanish musical traditions emerged, with Spanish lyrics set to French airs, reflecting Spain's significant influence at the French court. Between 1578 and 1629, French court music collections included 36 Spanish airs, with one more published in 1668, totaling 37 Spanish airs de cour.

Le Bal, Abraham Bosse, 1634, Musée du Louvre.

These airs were published during different periods of Franco-Spanish relations. Fabrice Caiétain's (1578) and Guillaume Tessier's (1582) airs were released during the final decades of Spanish hegemony. Charles Tessier's (1604) and Gabriel Bataille's (1608) airs appeared during the reign of Henry IV, a period marked by conflict between the two countries. Bataille’s airs from 1614 were published before Anne of Austria’s arrival. Antoine Boësset’s airs (1617 and 1624) and Etienne Moulinié’s (1625-26 and 1629) were published during Anne of Austria’s reign, a time of rising tension that preceded the war beginning in 1635.

They appear in various settings, including solo voice with lute or polyphonic versions for three, four, or five parts. Some airs are repeated in both polyphonic and solo settings. While most polyphonic parts have survived, some, such as the countertenor partbook for Guillaume Tessier's 1582 collection, are lost.

As early as 1578, Fabrice-Marin Caiétain published his collection Second livre d'airs, chansons, villanelles napolitaines & espagnolles, which included two four-part Spanish airs: “Falsa mes la spiga” and “Madre à l’amor.”

Second livre d’airs, chansons, villanelles napolitaines & espagnolles mis en musique à quatre parties par Fabrice Marin Caietain, Paris: Adrian Le Roy et Robert Ballard, 1578.

Guillaume Tessier followed suit in 1582 with his Premier livre d'airs tant français, italien qu’espagnol (reprinted in 1585), introducing three Spanish airs: ⏵︎ “No ay en la tierra,” “De unos ojos bellos,” and “Como harán dos.” Tessier’s Spanish airs featured simpler verses, assonant rhymes, and refrains, in contrast to the more sophisticated French texts. Musically, they employ the ternary rhythm with hemiola, characteristic of Spanish music and relatively rare in French songs at the time. Spanish accentuation, markedly different from French, is consistently respected in a predominantly syllabic texture. Charles Tessier included two Spanish pieces in his Airs et villanelles (1604): “Alla nel monte” and “Una pastor’ hermosa,” for four and five voices, respectively. This trend of incorporating Spanish airs would continue throughout the 17th century.

Premier livre d’airs tant francois, italien, qu’espaignol reduitz en musique à 4 et 5 parties par M. G. Tessier, 1re éd.: Paris: A. Le Roy et R. Ballard, 1582 (2 éd., 1585).

The first Spanish air to appear in Bataille’s collections was the anonymous ⏵︎ “Passava amor su arco desarmado,” with a poem by Jorge de Montemayor from Los siete libros de la Diana (1559), published in Airs de différents auteurs (1608). However, it is his 1609 collection, Second livre d’airs de différents auteurs (1609), that contains the largest number of Spanish airs. This collection includes ten airs de cour for solo voice and lute, such as ⏵︎ “Vuestros ojos tienen d’amor” and ⏵︎ “El baxel esta en la playa.” These airs adhere to the harmonic tradition of the French corpus in which they are included: while the majority of French airs are composed in a minor mode (especially in G), seven of the Spanish airs are in G minor and three in F major. Like the French airs, the Spanish ones almost completely lack ornamentation, and the lute is limited to accompanying the melody without significant additions. However, they exhibit important differences: the melodic simplicity of the Spanish airs is more pronounced, their range is more restricted, melodic movements are often conjunct, and melodic turns tend to repeat. Parallel sources found in Italy and Spain suggest that this repertoire predates its appearance in France, indicating that these authors merely incorporated it into their French collections, adding an exotic touch that was becoming fashionable at the French court.

Airs de différents autheurs, mis en tablature de luth par Gabriel Bataille. Second livre, Paris: Pierre Ballard, 1609.

Bataille’s Airs de différents auteurs, livre V (1614) includes two additional Spanish airs: “Yo soy la locura” and “Si sufro por ti morena.” ⏵︎ “Yo soy la locura,” by Du Bailly, features a brief introduction for lute followed by a strophic setting of the Spanish text. The title, “Passacalle, La Folie,” suggests a passacaglia, although the introductory lute solo does not adhere to any folia pattern; it precedes the folia, as indicated by the title. ⏵︎ “Si sufro por ti morena” is Bataille’s own composition. The solo voice and lute accompaniment version of “Si sufro por ti morena” is derived from the four-voice rendition published a year earlier by Pierre Ballard in the compilation Airs à quatre de différents autheurs (1613).

Henri du Bailly's air Yo soy la locura, from Airs de différents autheurs, mis en tablature de luth par Gabriel Bataille, Cinquième livre, Paris: Pierre Ballard, 1614.

Musical settings of Spanish texts were very well received, as evidenced by their prominence in collections of airs de cour. Boësset contributed to this trend with two notable airs: ⏵︎ “Una musica le den” (1617) and ⏵︎ “Frescos ayres del prado” (1624). For these Spanish airs, Boësset likely harmonized popular tunes that were well known among his contemporary Hispanophiles. “Una musica” was probably composed for the entertainment of Queen Anne of Austria and her Spanish entourage. This poem, rich in Gallicisms, depicts a tiff between Pedro and Joaníqua, characters who frequently appear in popular Spanish theatre.

Boësset's Frescos ayres del prado

from Quatrième livre d’airs de cour à quatre et cinq parties, Paris, Pierre Ballard, 1624

Anon. Frescos ayres del prado

from Firenze, Biblioteca Riccardiana, Ricc. 2793.

“Frescos ayres del prado,” published in both polyphonic and solo versions with lute accompaniment, exhibits characteristics of the Spanish polyphony tradition as well as those of Spanish songbooks from the time, evoking the refinement of the tonos humanos of the court of Philip IV. Musically, the first part is vertical with a ternary rhythm that shifts to binary in the final measures, possibly conveying joy and swiftness characteristic of a bucolic atmosphere. The second part is longer, featuring contrapuntal passages, alternating rhythms, syncopation, and dissonances that describe the protagonist's sadness. While the lute version retains the main melody, the string accompaniment lacks the polyphonic richness found in the second verse. These airs demonstrate Boësset’s incorporation of Spanish elements, such as rhythmic shifts and syncopation, into his compositions.

The first Spanish air published by Moulinié was “Embiame mi madre,” featured in Airs de cour à quatre et cinq parties (1625). Here, a young maiden is sent alone by her mother to fetch water, her voice reflecting a mix of mischief and astonishment. The theme of an unwise mother sending her daughter for water appears in both Castilian and Portuguese poetry, as seen in the verse: “Embiame mi madre por agua sola: ¡mirad a qué hora!” (Anon., BNE, Mss. 17557, f. 81v.). Traditional poetry often portrays a young girl going to the fountain and returning wounded by love, as in: “Enviárame mi madre por agua a la fuente frida, vengo del amor herida.” Another textual concordance is found in “Baile de las Cantarillas” from Colección de bailes, mojigangas, entremeses y coplas, BNE, Mss. 16291, p. 220. Here, the “Graciosa” enters with a small jug and sings: “Embiame mi madre por agua y sola. Mirad á qué hora, moza y hermosa.” Meanwhile, the charming “Bezón” enters with a pitcher and sings: “Embiame mi padre solo, y por vino, mirad, que aliño muchacho, y lindo.”

Moulinié’s Embíame mi madre

from Airs de cour à 4 et 5 parties, Paris: P. Ballard, 1625.

Baile de las Cantarillas

from Biblioteca Nacional de España, Mss. 16291, p. 220.

Queen Anne of Austria, daughter of Spain and wife of Louis XIII, brought a strong Spanish influence to France, rejuvenating Spanish fashions. Her influence likely contributed to the sustained popularity of Spanish airs in France. Although Italian language and literature were held in greater esteem, many courtiers hummed Spanish songs or used Spanish proverbs to appear fashionable. Spanish sarabands and passacailles also made their way to courtly dance floors, as noted by Mersenne in Harmonie Universelle, 1636.

Airs de cour avec la tablature de luth et de guitare de Estienne Moulinié, Troisiesme livre, Paris: Pierre Ballard, 1629.

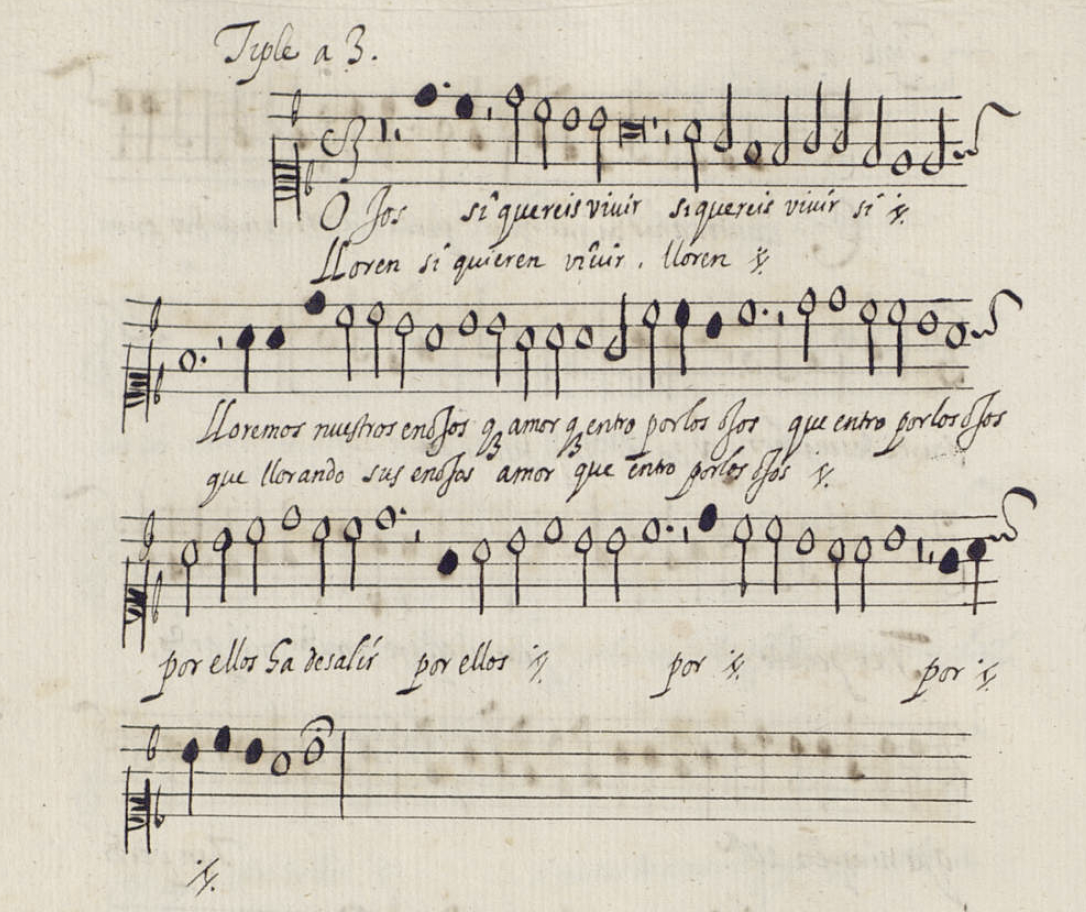

In 1626, Moulinié published six polyphonic Spanish airs, though only the soprano part of these works is extant. ⏵︎ “Ojos si quereis vivir” demonstrates the composer’s ability to alternate between binary and ternary rhythms and features chromaticism and melismatic passages that enhance the text's vividness. The complex rhythmic structure and ornamentation of “Ojos si quereis vivir” represent a stylistic shift from the earlier, simpler Spanish airs. While alternative sources for this repertoire are scarce, the version of “Ojos si quereis vivir” from the National Library of Madrid stands out. Despite textual variations and differences in rhythmic structure compared to Moulinié's version, the melodic line remains consistent, indicating a shared musical tradition between Spain and France during that period. ⏵︎ “Si negra tengo la mano,” from the same collection, uses the metaphor of the heart being carbonized to symbolize the intense passion of love, a recurring theme in 17th-century poetry and music. This imagery, present in both popular songs and courtly poetry, portrays the heart as turning black like wood transformed into charcoal by fire. The song's simplicity, syllabic melody, and strict ternary rhythm set it apart from the typical French airs of the period.

Ojos si quereis vivir

from VII Livre d'Airs de cour et de différents autheurs,1626.

Ojos si quereis vivir

from Biblioteca Nacional de España, Ms M 1370.

Also in 1626, Luis de Briceño published his Método muy facilísimo para aprender a tañer la guitarra a lo español in Paris. This collection, written in Castilian cifras, features dances and popular songs in the rasgueado style, using strummed guitar chords to accompany melodies. The songs are provided only with text and alfabeto chords, lacking the melodies themselves. Briceño’s method played a key role in disseminating Spanish guitar techniques in France and influencing the courtly airs of the time. The collection begins with a ‘Tono francés’ set to a Spanish text, ⏵︎ “Ay amor loco.” ⏵︎ “Serrana si vuestros ojos” is featured under the headline “Otras Folias Diferentes y Buenas.” Various Spanish and Italian texts intended to be sung sopra folia, accompanied by guitar chord letters, appear in Italian manuscript sources from the first half of the 17th century, such as ⏵︎ “Si queréis que os enrrame.”

Ay amor loco, from Metodo mui facilissimo para aprender a tañer la guitarra a lo espagnol, Paris, 1626.

Moulinié was known as a musician well-versed in fashion, open to all its trends, and capable of adapting to various kinds of texts. He published five more Spanish airs accompanied by guitar in his 3ème livre d'airs mis en tablature de luth (1629). Like his predecessors, Moulinié's Spanish airs were set to Spanish texts but composed with French-style music. His expertise with the rasgueado technique added rhythmic precision to his compositions, while his use of simple harmonies captured the rustic charm of Spanish songs, as seen in the air ⏵︎ “Orilla del claro Tajo.” A native of Languedoc, the musician may have spoken Spanish. He might even have been the author of some of these texts composed in honor of the royal couple. The second stanza of ⏵︎ “Repicavan las campanillas” includes a reference to “Anna y Luis.”

Repicavan las campanillas

from Airs de cour avec la tablature de luth et de guitare de Estienne Moulinié, Troisiesme livre, Paris: Pierre Ballard, 1629.

The last published Spanish air de cour from this period was Moulinié’s “Clori sobr'el lido del mar” in Sixième livre d’Airs à 4 & 5 parties avec la basse continue (1668). Unfortunately, only the superius part has survived; the other parts need to be reconstructed.

Air Espagnol Clori sobr’el lido del mar

from VI Livre d'Airs à quatre parties, Paris, Robert Ballard, 1668.

This cross-cultural musical dialogue between France and Spain resulted in a unique and delightful repertoire. As a great admirer of this tradition, I have dedicated myself to editing and reconstructing a substantial portion of these airs. I am continuing to work on transcribing, editing, and, in some cases, arranging and reconstructing these works. Meanwhile, some are already available on my YouTube channel in this playlist, and you can purchase the scores in my shop on this website.

References:

Baron, J. H. (1977). Secular Spanish solo song in non-Spanish sources, 1599-1640. Journal of the American Musicological Society, 30(1), 20–42.

Devoto, D. (1994). Un millar de cantares exportados. Bulletin Hispanique, 96(1), 5-115.

Durosoir, G. (1991). L'air de cour en France: 1571-1655. Belgium: Mardaga.

Martínez Torner, E. (1966). Lírica hispánica: Relaciones entre lo popular y lo culto. Spain: Editorial Castalia.

Mujica Lafuente, A. B. (2019). Les airs de cour en espagnol du Second livre d’airs mis en tablature de luth par Gabriel Bataille (Paris, 1609) : Un cas de transfert culturel? [Mémoire].

Rico Osés, C. (2014). Los "airs de cour" en español publicados en Francia 1578-1629. Cuadernos de música iberoamericana, 27, 49-69.