Nicholas Lanier and His Songs: Tradition and Innovation in 17th-Century English Music

Nicholas Lanier (1588–1666) was a central figure in 17th-century English music, renowned as a composer, singer, lutenist, and painter. A friend of prominent artists such as Rubens and Van Dyck, he was the first Master of the King’s Music under Charles I. Lanier introduced significant innovations to English music, notably influenced by Italian monody, while maintaining elements of the traditional Elizabethan style, creating a blend of innovation and tradition in his work.

Born into a prominent family of French and Italian court musicians, Lanier's career flourished through his roles as a lutenist, singer, and viol player. According to Roger North, Lanier's travels to Italy between 1625 and 1628, during which he acquired art for the King, exposed him to the Italian monodic style and deeply influenced his compositions. This journey marked a turning point in his music, leading to the introduction of recitative in English song. Daniel Nys reported to the Mantuan court that Lanier, a virtuoso on the bass viol, had left Venice for Verona and Mantua and was heading to Rome “under the pretext of buying pictures.” Vincenzo Giustiniani's Discorso sopra la musica de' suoi tempi (1628) also praises Lanier’s skill on the lyra viol.

Portrait of Nicholas Lanier (1588-1666). (© The Weiss Gallery, London)

Although Lanier is credited with introducing Italian monody to England, Ian Spink notes that his works do not follow a consistent developmental pattern. His songs include both the light Elizabethan pastoral style and a more serious declamatory idiom. Around thirty of his songs survive, mostly in manuscripts compiled by music enthusiasts in the 17th and 18th centuries, leading to variations between different versions.

Dating Lanier’s music is challenging, but certain pieces provide clues. His earliest known song, “Bring away this sacred tree” (1612), was composed for Campion's Masque of Squires. The melody was reused in ⏵︎ “Weep no more, my wearied eyes”, which appears in several early manuscripts.

In Jonson’s Masque of Augurs (1622), Apollo’s song ⏵︎ “Do not expect to hear” illustrates a more melodic application of rhythmic groupings, reflecting the increasing appeal of the declamatory air by that period. Sung by Apollo towards the end of the masque directly to the King, the song begins with the lines: "Do not expect to hear of all/Your good at once," and it offers the usual lavish praise, ending with:

It is enough your people learn

The reverence of your peace,

As well as strangers do discern

The glories of th'increase;

And that the princely augur here, your son,

Do by his father's lights his courses run.

Although Lanier may have performed as Apollo, his principal role in this instance was providing the music, which, as Jonson noted, he shared with Ferrabosco. While the complete music for Augurs is unknown, "Do not expect" is certainly not a bold experiment in stilo recitativo. Although it is dramatic and effective, it is even less declamatory than the earlier "Bring away this sacred tree." The text is entirely subordinate to the music, contrary to the principles of recitative. Based on this single song, it seems Lanier had not yet fully embraced the true stilo recitativo.

Lanier and other court singers often employed elaborate ornamentation and non-metrical delivery, producing a sound that sometimes resembled true recitative. ⏵︎ “I was not wearier,” a setting from Jonson's The Vision of Delight (1617), features a florid vocal line. The melody is preserved only as a profusely ornamented cantus in a manuscript. The original version is lost, leaving only this heavily embellished version. At key points in the lyric ("then I am willing," "but I am urged"), the melody's structure is preserved.

I was not wearier, from British Library, MS Egerton 2013, fol. 45v.

One of Lanier's most famous works, Hero and Leander, is noted for being one of the first English recitatives, influenced by early Italian models. Roger North, in his Musicall Grammarian, states that Lanier composed ⏵︎ Hero and Leander (“Nor com’st thou yet”) shortly after returning from Italy (1625–28), following a picture-buying expedition for Charles I. North recounts that "the King was exceedingly pleased with this pathetick song and caused Lanneare often to sing it, with his hand upon his shoulder."

Hero and Leander, from British Library, Add. MS 14399, ff.22v-28r.

In Lanier's imitation of the Monteverdian lamento, Hero's Complaint to Leander, the syllabic vocal line breaks out, under pressure, into a rare melisma, in which fleeting patterns in the bass suggest Hero's erotic obsession, and dissonant harmonic movement suggests the internal strife of her emotions. This extended scene, where Hero’s emotions evolve from frustration at Leander's delay to hope as she imagines him making his way across the Hellespont, and finally to grief when she discovers his lifeless body, unfolds with the depth and drama of a small-scale operatic narrative.

Lanier's declamatory ayre and recitative style did not cause a sudden change in English song forms but coexisted with earlier styles and even influenced them. Composers like Robert Johnson, Robert Ramsey, and William Webb created works blending traditional lutenist ayre with declamatory continuo song. Johnson's ⏵︎ “Care-charming sleep”, Webb's ⏵︎ “Powerful Morpheus”, and Ramsey's ⏵︎ “Go perjur'd man,” though more melodic than Lanier's pieces, incorporate vocal declamatory touches and a looser musical structure, treating phrases as nearly independent units.

Love's Constancy, from Select Ayres and Dialogues, Second Book, Playford, 1669.

Further fruit of Lanier's Italian visits may be seen in ⏵︎ “No more shall meads be decked with flowers” (Love’sContancy)—one of Carew's lyrics that Lawes did not set, perhaps because Lanier's setting was already well known. Lanier treats this as a ground, repeating a chaconne-type bass for four verses while varying the tune. (One literary source even labels the poem 'Ciacono'.) However, the formal significance of Lanier's song was probably not appreciated at first, as two manuscript sources, obliviously and independently of each other, alter the bass during the course of the song, thus destroying its essential feature. It was not until Playford printed it that the bass was restored to what must have been its original form or something like it. Basically, the conventional tetrachord of the chaconne bass is combined with a cadential progression. (Later, John Blow followed suit with ⏵︎ “Lovely Selina, innocent and free,” published in Playford’s Choice Ayres,1683.)

Nicholas Lanier, c.1644 (oil on canvas) by Nicholas Lanier. (Faculty of Music Collection, Oxford University/The Bridgeman Art Library)

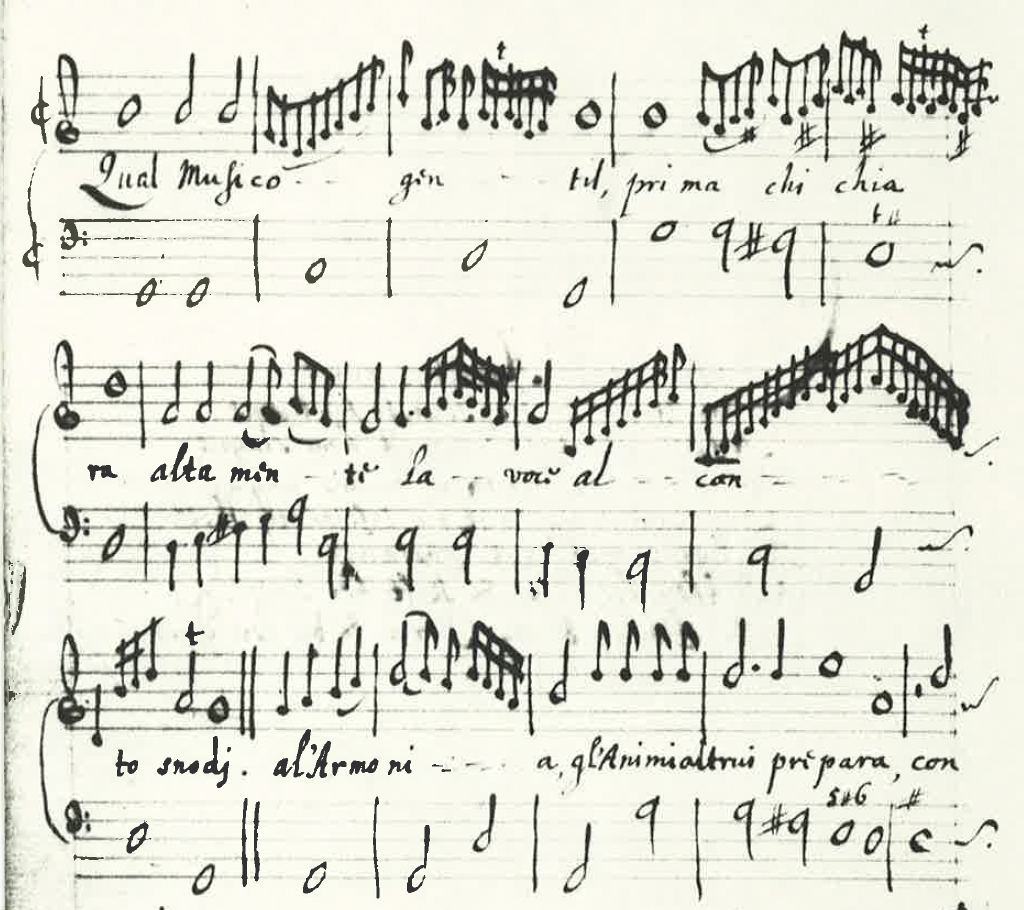

Lanier’s Italian setting of Torquato Tasso’s ⏵︎ “Qual musico gentil” from Gerusalemme Liberata presents an interesting blend of simplicity and complexity. The melodic framework is remarkably simple, supported by a rudimentary bass line, but the true effect of the piece comes from its profuse ornamentation. The divisions are extensive, spanning a wide range, yet despite the virtuosity, the music maintains a fluidity and grace characteristic of the Italian style.

Qual musico gentil, from British Library Add. MS 11608, f.27v.

Many of his songs continue the pastoral, idyllic themes of earlier composers like Campion and Ferrabosco. These works, characterized by simple melodies and diatonic progressions, were popular among amateur musicians and demonstrate Lanier’s versatility in composing both accessible and sophisticated music.

Spink notes that, unlike Henry Lawes, Lanier didn’t seem to connect with the themes of Cavalier verse, which he rarely set to music, and only in its most conventional form. Instead, he was drawn to Elizabethan poets like Campion, setting verses such as ⏵︎ “Thou art not fair for all thy red and white” and ⏵︎ “Fire, lo here I burn.” In writing tunes for this type of verse, Lanier was fairly successful.

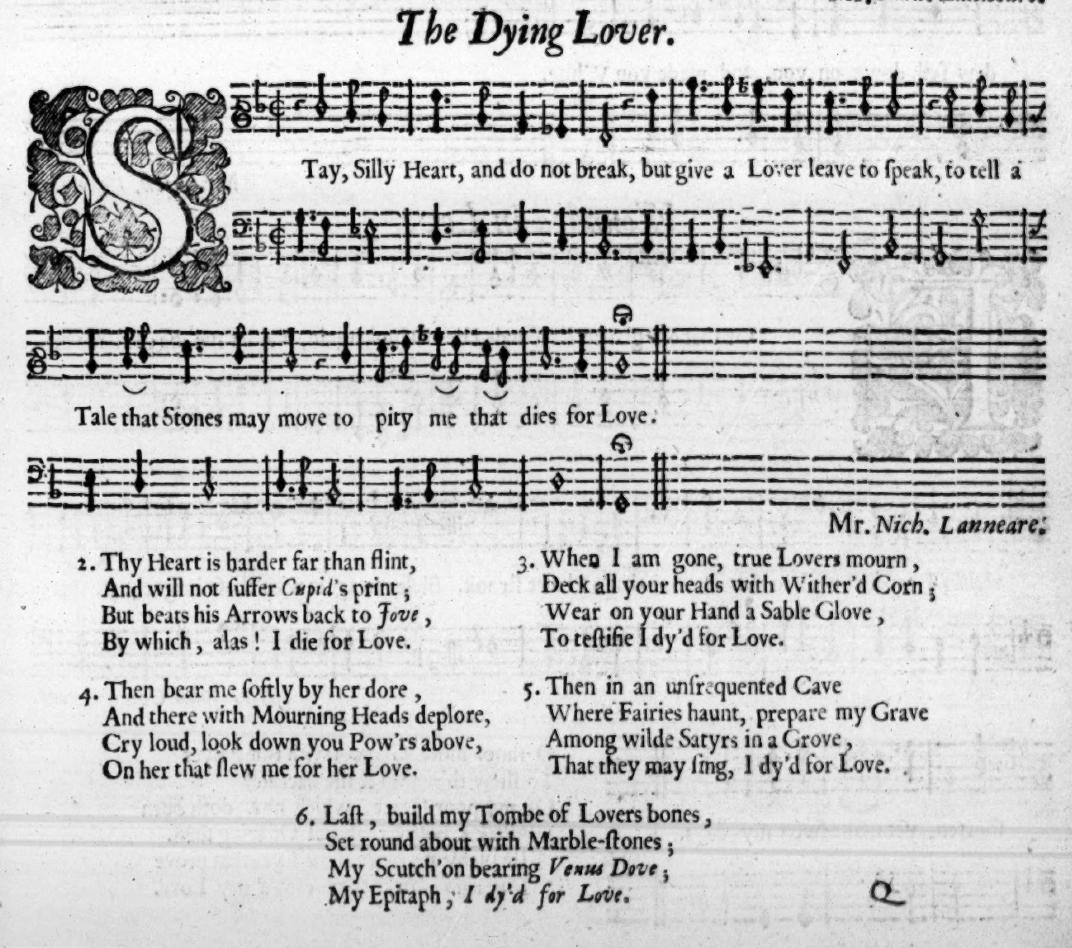

In the wistful and delicate ⏵︎ “Stay, silly heart,” the lightness of the verse excuses the lack of literary sophistication, as the melody compensates for it, giving the words and music a nearly ballad-like feel.

Stay, silly heart, from Select Ayres and Dialogues, Playford, 1669.

Raleigh's ⏵︎ “Like hermit poor,” a more serious song, recalls some of the features of “Bring away this sacred tree.” Compared to Alfonso Ferrabosco's setting of the same text, it serves as a strong example of the early declamatory ayre.

Lanier’s contributions were recognized by his contemporaries, including poets Robert Herrick and Lucius Cary, Viscount Falkland. Herrick, in his poem To M. Henry Lawes, the excellent Composer of his Lyricks, alludes to Lanier:

Touch but thy Lire (my Harrie) and I hear

From thee some raptures of the rare Gotire.

Then if thy voice commingle with the String

I hear in thee rare Laniere to sing…

Cary also mentions Lanier in his Elegy on the Death of Sir Henry Morison:

Now all is lost that is upon me plac'd

As he a pheasant had, that had no taste,

As if Laniere should to a deaf one sing,

Or I should Helen to a blind man bringe…

John Donne references Lanier in the preface to his Poems, Written by the Right Honorable William Earle of Pembroke (1660), noting that some of the poems were obtained from Lanier and Henry Lawes. Donne writes that Lanier "by his great skill gave a life and harmony to all that he set."

P.J. Mariette notes in his Abecedario, VI, p. 329, that he was a 'handsome man with a countenance full of gentleness, and who greatly resembles that of his master, the king.' Van Dyck painted a portrait of Lanier in Italy, and also painted him a second time as David playing the harp.

Nicholas Lanier, painting by van Dyck, 1632, Kunsthistorisches Museum.

Ian Spink remarks that while John Donne may have been overly generous in this praise, Herrick’s reference to "rare Laniere" perhaps offers a more measured view of his contributions.

Lanier's ability to bridge the gap between old and new musical styles, introducing Italian influences while remaining rooted in English traditions, solidified his legacy as a significant figure in 17th-century English music.

Feel free to check out my ⏵︎ YouTube playlist dedicated to his songs. Modern scores are available for purchase on my website shop!

References:

Albright, D. (2007). Musicking Shakespeare: A Conflict of Theatres (Eastman Studies in Music) (Eastman Studies in Music). United States: University of Rochester Press.

Callon, G. J. (Ed.). (1994). Nicholas Lanier: The Complete Works. United Kingdom: Severinus Press.

de Hevesy, A. (1936). Rembrandt and Nicholas Lanier. The Burlington Magazine for Connoisseurs, 69(403), 153–154. http://www.jstor.org/stable/866519

Hebbert, B. M. (2010). A New Portrait of Nicholas Lanier. Early Music, 38(4), 509–522. http://www.jstor.org/stable/40963052

Jones, E. H. (1989). The Performance of English Song: 1610-1670. United Kingdom: Garland Pub.

McD. Emslie. (1960). Nicholas Lanier’s Innovations in English Song. Music & Letters, 41(1), 13–27. http://www.jstor.org/stable/729684

Spink, I. (1959). Lanier in Italy. Music & Letters, 40(3), 242–252. http://www.jstor.org/stable/729390

Spink, I. (1986). English Song. London: Batsford.

Wilson, M. (2017). Nicholas Lanier: Master of the King's Musick. United Kingdom: Taylor & Francis.